Previously on The Undeniable Ruth: I had just finished the 112-mile bike ride on the grueling hills of Lake Placid. After I handed off my bike to a volunteer, I walked into the transition area, grabbed my run gear bag, and made another pit stop at a porta-potty before heading into the women’s changing tent.

Transition Two (T2)

After sitting on my bike for nearly 8 hours, my quads and butt did not want to sit on a chair to change my shoes, but I forced them to do it. I also exchanged my cycling helmet for the Ironman Arizona 70.3 hat that Coach David gave me after he did the race in 2018.

I peeled off my cycling socks and placed my bare feet on a small towel from my bag. Then I sprinkled them with baby powder, making sure both sides of my feet were dry before pulling on my running socks with built-in arch support and then my shoes.

I snapped my race belt around my waist with a click. Our race numbers were given out sequentially based on when we checked it, but volunteers customized them upon request. Most people opted to get their name, but I asked for “Baby Duck.” This was a nickname my gymnastics coach Rocky used for his gymnasts, much like how someone would use “sweetie” or “buddy.”

As I prepared for the run, I heard Mike Reilly’s voice coming through the speakers across the transition area, announcing people’s names as they crossed the finish line.

There were people finishing the race, and I literally had a marathon (26.2 miles) to go.

There were other athletes who weren’t as lucky as me. Some of them DNFed during the bike due to injury or they opted to stop because they knew they wouldn’t make the cut off time. (During an Ironman race, not only do you have to finish in under 17 hours, but each section has its own cut-off time.) Behind me in the tent was a woman lying on the ground being tended to by medics. Her race day was done.

I sprayed myself down with sunblock one more time, put my sunglasses back on my face, and headed out.

Running a Marathon with Sore Legs

In every picture of me running during this race, my feet are barely off the ground. That’s because it felt like I could barely lift them.

The run course was 2 loops of 13 miles each followed by a final turn into what was the Olympic outdoor speed skating track to reach the finish line. Within each loop were several out-and-back portions.

Not as severe as the bike portion, the run course had several hills, which was nice on the way down, but not so nice going back up. During the first loop, I walked only when going up the steepest hills, and even then, I power walked.

Even though my body hurt and I had miles ahead of me, I was still smiling. A spectator looked at me quizzically and said, “You’re having fun, aren’t you?” I responded with “Fun is what you bring with you,” my favorite quote from Drew Barrymore in Riding in Cars with Boys.

Aid Stations = Buffets

Ironman does an impressive job of taking care of its athletes, and nowhere is this more apparent than the aid stations during the run. They were placed every 1-1.5 miles where volunteers offered water, Gatorade, Coca-Cola, Red Bull (they were a sponsor), chicken broth, electrolyte gels, fruit, chips or pretzels, and granola bars. Whatever you needed, it was available.

My stomach does not want to eat when I work out. I ate a gel at Miles 5, 10, and 15, and took a hit of BASE salt from my vial every mile. I mostly drank Gatorade at every aid station. I tried the Coke a few times to treat myself to the sugar but realized my body didn’t like that. There was a final table at each aid station that held cups of ice cubes. “What’s this for?” I asked the volunteer. She responded, “Put it in your bra.” I shrugged and thought, “When in Rome,” grabbed a cup of ice, and dumped it into my sports bra. It did help me feel cooler, and I regularly reached in to grab a cube to suck on between aid stations.

I Have to Poop Again?!

Along with the buffet, each aid station also had 2 porta-potties. As I approached the aid station at Mile 5, I felt a familiar sensation in my stomach.

Seriously?! How do I have anything left in my system?

I hadn’t seen Coach David since he passed me early on during the bike portion of the race. Stepping into the porta-potty, I figured it would be just my luck that he’ll pass me going the other direction while I’m going to the bathroom.

Using a porta-potty after it’s been available to literally thousands of racers and baked in the afternoon sun was an assault to the senses. Getting my triathlon onesie back up my skin that was slimy from sweat while standing in a warm, smelly, plastic box was a bit of an ordeal.

Catching Coach David

Throughout the run, I was constantly watching for Coach David. I scanned the group for an athlete wearing a neon yellow jersey and a backpack. (It’ll make sense later.)

Finally, near Mile 13, I saw him as we passed each other going in opposite directions. (I called it! He must have passed me when I was in the porta-potty.) I knew he knew I was ok because he’d been tracking me on the race app all day, and it alerted him each time I went over a race sensor.

I later learned he was worried about me and relieved to finally put eyes on me. Apparently, I dropped off the app for a bit.

David was doing a run/walk, and I pushed myself to run even faster, determined to catch up with him. I finally caught up with him at Mile 17 and we took a selfie – still smiling.

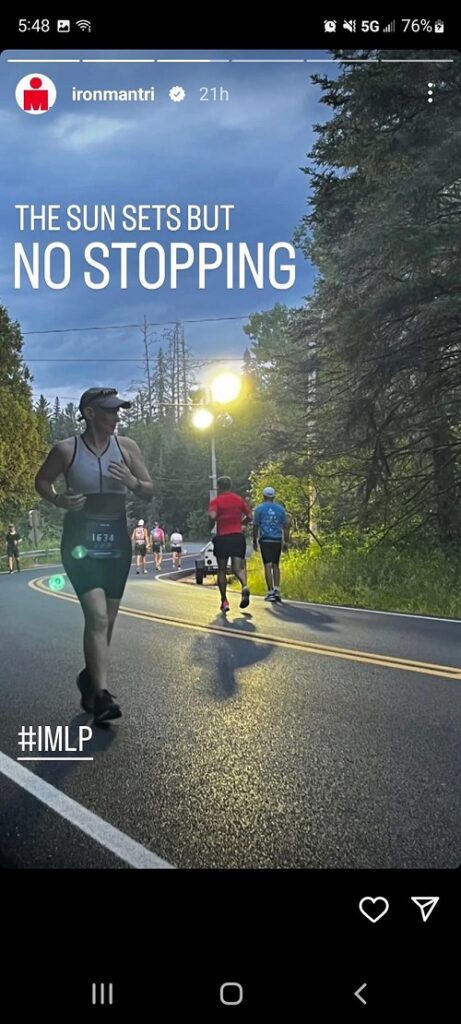

I continued to run ahead of David. The sun was going down and I moved my sunglasses to the top of my head. One of the volunteers on a golf cart drove through the course, turning on the portable lights to illuminate the road for those of us who would be finishing the race after dark.

Someone from Ironman snapped a photo of me on the road and put it on their Instagram story. That was so cool to see after the race.

Around Mile 19 or 20, David and I passed each going in opposite directions again. He yelled to me, “In 45 minutes, you’re going to be an Ironman!” (Looking back, that wasn’t accurate given my pace, but I appreciated the sentiment.)

Race Math

It started on the bike. I determined when I was 100 miles into the bike, I was over 70% done with the total distance of the race. When I finished the bike, I was over 80% done.

With every passing mile of the run, I recalculated how much of the race I had left. Six miles to the finish line meant I had only 1/23 of the race left. Five miles to the finish line meant I had only 1/28 of the race left to do. It gave my brain something to do and distracted me from my sore legs and feet.

For the last portion of the race, whenever there was any incline in the course, I walked. I had plenty of time before the 17-hour cut off, and I wasn’t going to torture myself more than necessary.

As I jogged and walked along, I saw others who couldn’t finish the race. Some were driven back to the transition area on golf carts with foil blankets wrapped around them to keep warm. I saw another racer puking on the side of the road. There were several people who looked like they could only walk the last remaining miles. I wondered if they were at risk of not making the 17-hour cut off.

Out of the 2,273 people who started Ironman Lake Placid that day, 456 DNFed because they either couldn’t finish the race or they didn’t finish it in time.

The Finish Line

Some people cry when they cross the finish line at Ironman. Around Mile 25, I felt my emotions start to bubble up. When I made the final turn towards the finish line, tears welled up in my eyes.

After nearly 3 years of training, 3 years of early morning workouts, training in the cold and the heat, managing sore muscles and injuries, and overcoming mental setbacks, I made it.

My sore feet hit the red and black Ironman carpet as I approached the finish line, and I heard Mike Reilly’s voice: “You finally got here, huh Ruth? From Phoenix, you are an Ironman!” (He knew from my bio that I filled out when I signed up for the race that my Ironman races in 2020 and 2021 cancelled due to COVID.)

I raised my arms as I crossed the finish line – 15 hours, 21 minutes, 42 seconds after I plunged into Mirror Lake that morning to start this 140.6-mile journey. My race started at 6:39 a.m., and I finished it right at 10 p.m.

I was an Ironman.

Overcome with joy and gratitude, I burst into tears.

Thankfully, David paid for his family to be VIPs so they could meet him at the finish line and his wife, Janet, could put his medal around his neck. She wrapped her arms around me in a big hug and told me that David was only a few minutes behind me.

I got my medal, took a finisher photo with the Ironman backdrop, and walked into the athletes’ post-race area where a volunteer handed me a bottle of water. Another volunteer doublechecked that I was ok, and I hadn’t been crying in pain.

At 15 hours, 24 minutes, 53 seconds after we started the race, I heard Mike Reilly’s voice again: “David Roher, He looks just like him! Look at him! David Roher, you are an Ironman! Tony Stark – right there!”

I watched as my coach crossed the finish line in his Ironman costume. That’s what was in the backpack. (He really does look remarkably like Robert Downey Jr.)

After he kissed his wife and said hello to his family, David and I gave each other a big hug, and of course, I started bawling like a baby again. Once I regained my composure, he excitedly said, “Let’s take a picture!” It’s so cute when he’s in proud coach mode.

Post-Race

Prior to the race, I paid for valet service so Tribike Transport (the company that transported my bike to and from the race) collected my bike and gear bags. I’d pick up my gear bags from them the following morning.

After the race, all I had to do was walk back to my hotel, which thankfully wasn’t far from the finish line. Unfortunately, it was also on a steep hill. My calves and quads screamed with every step. My body felt cold as my heart rate slowed and the adrenaline rush of the finish line wore off.

All I wanted a hot shower and to brush the film of Gatorade off my teeth. Oh my goodness, it hurt to bend down to untie my shoes. I posted a picture of my medal to Facebook, and I think I called my mom to let her know I survived the race.

There were pizza, French fries, and chips at the finish line, but it would be hours before my stomach would settle enough to eat anything. I climbed into bed. I was exhausted, but my body was so sore it was hard to get comfortable. It hurt to move, and it hurt to hold still.

At 2 a.m., I woke up ravenously hungry. I shuffled out of bed and ate 2 calorie bomb cookies before trying to get a few more hours of rest before I had to get up, pack my bags, and drive back to the airport to fly home.

Next week on The Undeniable Ruth: Ironman Lake Placid – The Supporters.